Family and Domestic Violence Fatality Review

Overview

This section sets out the work of the Office in relation to this function. Information on this work has been set out as follows:

- Background;

- The role of the Ombudsman in relation to family and domestic violence fatality reviews;

- Analysis of family and domestic violence fatality reviews;

- Issues identified in family and domestic violence fatality reviews;

- Recommendations;

- Major own motion investigations arising from family and domestic violence fatality reviews;

- Other mechanisms to prevent or reduce family and domestic violence fatalities; and

- Stakeholder liaison.

Background

The National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children 2010-2022 (the National Plan) identifies six key national outcomes:

- Communities are safe and free from violence;

- Relationships are respectful;

- Indigenous communities are strengthened;

- Services meet the needs of women and their children experiencing violence;

- Justice responses are effective; and

- Perpetrators stop their violence and are held to account.

The National Plan is endorsed by the Council of Australian Governments and supported by the First Action Plan: Building a Strong Foundation 2010-2013 (available at www.dss.gov.au), which established the ‘groundwork for the National Plan’, and the Second Action Plan: Moving Ahead 2013-2016 (available at www.dss.gov.au), which builds upon this work.

The WA Strategic Plan for Family and Domestic Violence 2009-13 (WA Strategic Plan) and Western Australia’s Family and Domestic Violence Prevention Strategy to 2022: Creating safer communities (the State Strategy), available at www.dcp.wa.gov.au, include the following principles:

- Family and domestic violence and abuse is a fundamental violation of human rights and will not be tolerated in any community or culture.

- Preventing family and domestic violence and abuse is the responsibility of the whole community and requires a shared understanding that it must not be tolerated under any circumstance.

- The safety and wellbeing of those affected by family and domestic violence and abuse will be the first priority of any response.

- Children have unique vulnerabilities in family and domestic violence situations, and all efforts must be made to protect them from short and long term harm.

- Perpetrators of family and domestic violence and abuse will be held accountable for their behaviour and acts that constitute a criminal offence will be dealt with accordingly.

- Responses to family and domestic violence and abuse can be improved through the development of an all-inclusive approach in which responses are integrated and specifically designed to address safety and accountability.

- An effective system will acknowledge that to achieve substantive equality, partnerships must be developed in consultation with specific communities of interest including people with a disability, people from diverse sexualities and/or gender, people from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds.

- Victims of family and domestic violence and abuse will not be held responsible for the perpetrator’s behaviour.

The associated Annual Action Plan 2009-10 identified a range of strategies including a ‘capacity to systematically review family and domestic violence deaths and improve the response system as a result’ (page 2). The Annual Action Plan 2009-10 sets out 10 key actions to progress the development and implementation of the integrated response in 2009-10, including the need to ‘[r]esearch models of operation for family and domestic violence fatality review committees to determine an appropriate model for Western Australia’ (page 2).

Following a Government working group process examining models for a family and domestic violence fatality review process, the Government requested that the Ombudsman undertake responsibility for the establishment of a family and domestic violence fatality review function.

On 1 July 2012, the Office commenced its family and domestic violence fatality review function.

It was essential to the success of the establishment of the family and domestic violence fatality review role that the Office identified and engaged with a range of key stakeholders in the implementation and ongoing operation of the role. It was important that stakeholders understood the role of the Ombudsman, and the Office was able to understand the critical work of all key stakeholders.

Working arrangements were established to support implementation of the role with Western Australia Police (WAPOL) and the Department for Child Protection and Family Support (DCPFS) and with other agencies, such as the Department of Corrective Services (DCS) and the Department of the Attorney General (DOTAG), and relevant courts.

The Ombudsman’s Child Death Review Advisory Panel was expanded to include the new family and domestic violence fatality review role. Through the Ombudsman’s Advisory Panel (the Panel), and regular liaison with key stakeholders, the Office gains valuable information to ensure its review processes are timely, effective and efficient.

The Office has also accepted invitations to speak at relevant seminars and events to explain its role in regard to family and domestic violence fatality reviews, engaged with other family and domestic violence fatality review bodies in Australia and New Zealand and, since 1 July 2012, has met regularly via teleconference with the Australian Domestic and Family Violence Death Review Network.

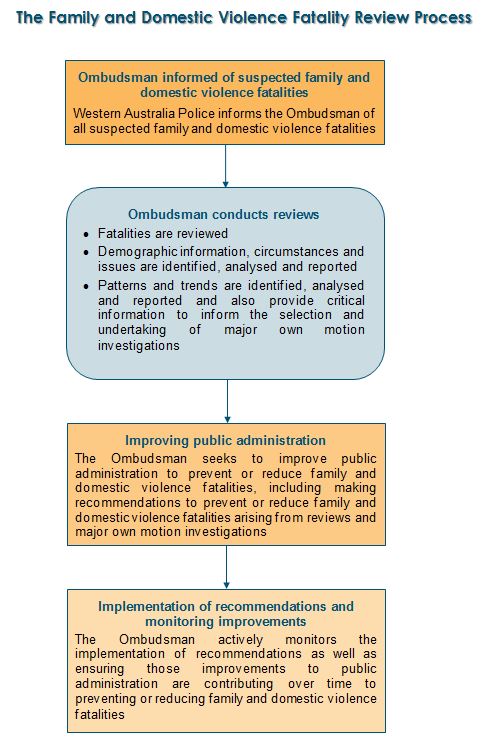

The Role of the Ombudsman in relation to Family and Domestic Violence Fatality Reviews

Information regarding the use of termsInformation in relation to those fatalities that are suspected by WAPOL to have occurred in circumstances of family and domestic violence are described in this report as family and domestic violence fatalities. For the purposes of this report the person who has died due to suspected family and domestic violence will be referred to as ‘the person who died’ and the person whose actions are suspected of causing the death will be referred to as the ‘suspected perpetrator’ or, if the person has been convicted of causing the death, ‘the perpetrator’. Additionally, following Coronial and criminal proceedings, it may be necessary to adjust relevant previously reported information if the outcome of such proceedings is that the death did not occur in the context of a family and domestic relationship. |

WAPOL informs the Office of all family and domestic violence fatalities and provides information about the circumstances of the death together with any relevant information of prior WAPOL contact with the person who died and the suspected perpetrator. A family and domestic violence fatality involves persons apparently in a ‘family and domestic relationship’ as defined by section 4 of the Restraining Orders Act 1997.

More specifically, the relationship between the person who died and the suspected perpetrator is a relationship between two people:

(a) Who are, or were, married to each other; or

(b) Who are, or were, in a de facto relationship with each other; or

(c) Who are, or were, related to each other; or

(d) One of whom is a child who —

(i) Ordinarily resides, or resided, with the other person; or

(ii) Regularly resides or stays, or resided or stayed, with the other person;

or

(e) One of whom is, or was, a child of whom the other person is a guardian; or

(f) Who have, or had, an intimate personal relationship, or other personal relationship, with each other.

‘Other personal relationship’ means a personal relationship of a domestic nature in which the lives of the persons are, or were, interrelated and the actions of one person affects, or affected the other person.

‘Related’, in relation to a person, means a person who —

(a) Is related to that person taking into consideration the cultural, social or religious backgrounds of the two people; or

(b) Is related to the person’s —

(i) Spouse or former spouse; or

(ii) De facto partner or former de facto partner.

If the relationship meets these criteria, a review is undertaken.

The extent of a review depends on a number of factors, including the circumstances surrounding the death and the level of involvement of relevant public authorities in the life of the person who died or other relevant people in a family and domestic relationship with the person who died, including the suspected perpetrator. Confidentiality of all parties involved with the case is strictly observed.

The family and domestic violence fatality review process is intended to identify key learnings that will positively contribute to ways to prevent or reduce family and domestic violence fatalities. The review does not set out to establish the cause of death of the person who died; this is properly the role of the Coroner. Nor does the review seek to determine whether a suspected perpetrator has committed a criminal offence; this is only a role for a relevant court.

Analysis of Family and Domestic Violence Fatality Reviews

Information on interpretation of dataInformation in this section is derived from the 73 reviewable family and domestic violence fatalities received from 2012-13 to 2015-16. As the information in the following charts is based on four years of data, care should be undertaken in interpreting the data. |

By reviewing family and domestic violence fatalities, the Ombudsman is able to identify, record and report on a range of information and analysis, including:

- The number of family and domestic violence fatality reviews;

- Demographic information identified from family and domestic violence fatality reviews;

- Circumstances in which family and domestic violence fatalities have occurred; and

- Patterns, trends and case studies relating to family and domestic violence fatality reviews.

Number of family and domestic violence fatality reviews

In 2015-16, the number of reviewable family and domestic violence fatalities received was 22, compared to 16 in 2014-15, 15 in 2013-14 and 20 in 2012-13.

Demographic information identified from family and domestic violence fatality reviews

Information is obtained on a range of characteristics of the person who died, including gender, age group, Aboriginal status, and location of the incident in the metropolitan or regional areas.

The following charts show characteristics of the persons who died for the 73 family and domestic violence fatalities received by the Office from 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2016. The numbers may vary from numbers previously reported as, during the course of the period, further information may become available.

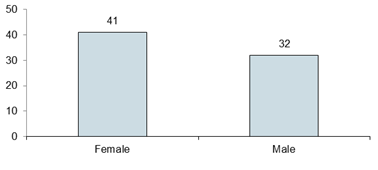

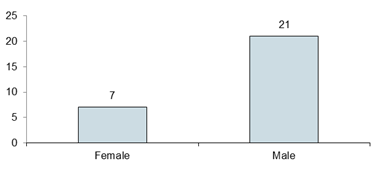

| Number of Persons who Died by Gender

|

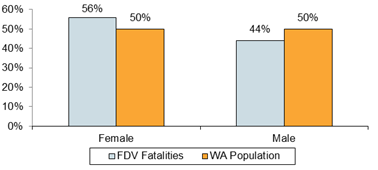

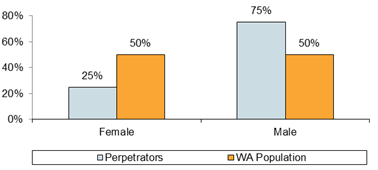

| Gender of Persons who Died Compared to WA Population

|

Compared to the Western Australian population, females who died in the four years from 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2016, were over-represented, with 56% of persons who died being female compared to 50% in the population.

In relation to the 41 females who died, 39 involved a male suspected perpetrator and two involved a female suspected perpetrator. Of the 32 men who died, six were apparent suicides, 15 involved a female suspected perpetrator, nine involved a male suspected perpetrator and two involved multiple suspected perpetrators of both genders.

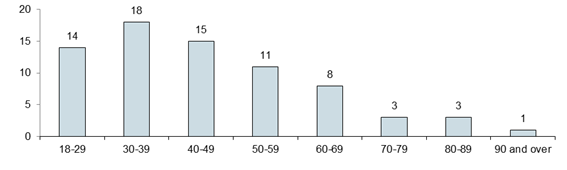

| Number of Persons who Died by Age

|

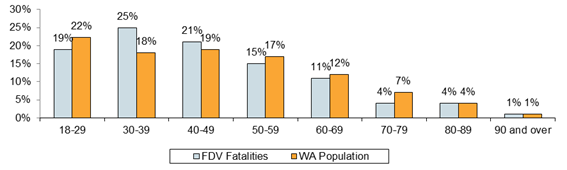

| Age of Persons who Died Compared to WA Population |

Compared to the Western Australian population, the age group 30-39 is over‑represented, with 25% of persons who died, compared to 18% of the population.

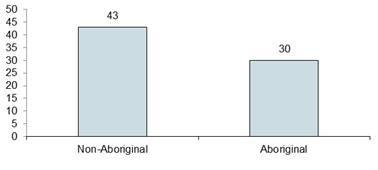

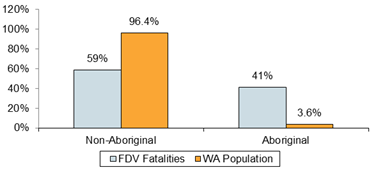

| Number of Persons who Died by Aboriginal Status

|

| Aboriginal Status of Persons who Died Compared to WA Population

|

Compared to the Western Australian population, Aboriginal people who died were over-represented, with 41% of people who died in the four years from 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2016 being Aboriginal compared to 3.6% in the population. Of the 30 Aboriginal people who died, 18 were female and 12 were male.

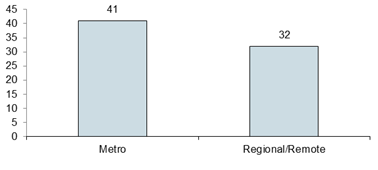

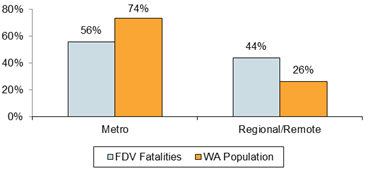

| Number of Persons who Died by Location of Fatal Incident

|

| Location of Fatal Incident Compared to WA Population

|

Compared to the Western Australian population, incidents in regional or remote locations were over‑represented, with 44% of fatal incidents in the four years from 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2016 occurring in regional or remote locations, compared to 26% of the population living in those locations.

The WA Strategic Plan notes that:

While there has been debate about the reliability of research that quantifies the incidence of family and domestic violence, there is general agreement that …

- [A]n overwhelming majority of people who experience family and domestic violence are women, and

- Aboriginal women are more likely than non-Aboriginal women to be victims of family violence (page 4).

More specifically, with respect to the impact on Aboriginal women in Western Australia, the WA Strategic Plan notes that:

Family and domestic violence is particularly acute in Aboriginal communities. In Western Australia, it is estimated that Aboriginal women are 45 times more likely to be the victim of family violence than non-Aboriginal women, accounting for almost 50 per cent of all victims (page 4).

In its work, the Office is placing a focus on ways that public authorities can prevent or reduce family and domestic violence fatalities for women, including Aboriginal women. In undertaking this work, specific consideration is being given to issues relevant to regional and remote Western Australia.

Information in the following section relates only to family and domestic violence fatalities reviewed from 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2016 where coronial and criminal proceedings (including the appellate process, if any) were finalised by 30 June 2016. |

Of the 73 family and domestic violence fatalities received by the Ombudsman from 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2016, coronial and criminal proceedings were finalised in 28 cases.

Information is obtained on a range of characteristics of the perpetrator including gender, age group and Aboriginal status. The following charts show characteristics for the 28 perpetrators where both the coronial process and the criminal proceedings have been finalised.

| Perpetrator by Gender

|

| Gender of Perpetrators Compared to WA Population

|

Compared to the Western Australian population, male perpetrators of fatalities in the years from 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2016 were over-represented, with 75% of perpetrators being male compared to 50% in the population.

Nine males were convicted of manslaughter and 12 males were convicted of murder. Five females were convicted of manslaughter, one female was convicted of unlawful assault occasioning death and one female was convicted of murder.

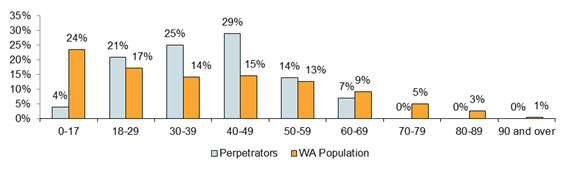

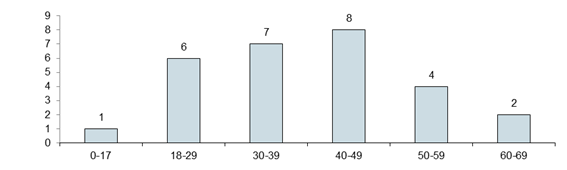

Perpetrator by Age |

| Age of Perpetrators Compared to WA Population

|

Compared to the Western Australian population, perpetrators of fatalities in the four years from 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2016 in the age groups 30-39 and 40-49 were over-represented, with 25% of perpetrators being in the 30-39 age group compared to 14% in the population, and 29% of perpetrators being in the 40-49 age group compared to 15% in the population.

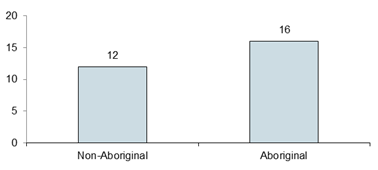

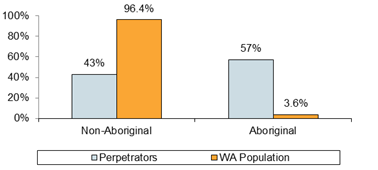

| Perpetrator by Aboriginal Status

|

| Aboriginal Status of Perpetrators Compared to WA Population

|

Compared to the Western Australian population, Aboriginal perpetrators of fatalities in the four years from 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2016 were over-represented with 57% of perpetrators being Aboriginal compared to 3.6% in the population.

In 14 of the 16 cases where the perpetrator was Aboriginal, the person who died was also Aboriginal.

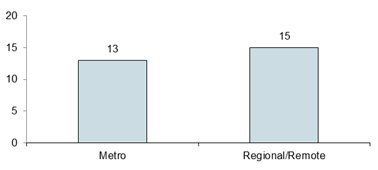

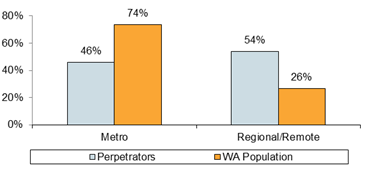

| Perpetrator by Location of Fatal Incident

|

| Perpetrators by Location of Fatal Incident Compared to WA Population

|

The majority of fatal incidents occured in regional or remote areas.

Compared to the Western Australian population, perpetrators of fatalities that occurred in regional or remote locations in the four years from 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2016 were over-represented, with 54% of perpetrators in regional or remote locations compared to 26% of the population living in those locations.

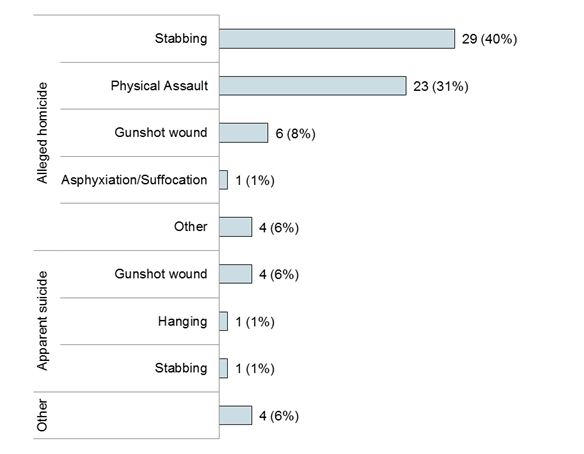

Circumstances in which family and domestic violence fatalities have occurred

Information provided to the Office by WAPOL about family and domestic violence fatalities includes general information on the circumstances of death. This is an initial indication of how the death may have occurred but is not the cause of death, which can only be determined by the Coroner.

Family and domestic violence fatalities may occur through alleged homicide or apparent suicide and the circumstances of death are categorised by the Ombudsman as:

- Alleged homicide, including:

- Stabbing;

- Physical assault;

- Gunshot wound;

- Asphyxiation/suffocation;

- Drowning; and

- Other.

- Apparent suicide, including:

- Gunshot wound;

- Overdose of prescription or other drugs;

- Stabbing;

- Motor vehicle accident;

- Hanging;

- Drowning; and

- Other.

- Other, including fatalities where it is not clear whether the circumstances of death are alleged homicide or apparent suicide.

The principal circumstances of death in 2015-16 were alleged homicide by stabbing and physical assault.

The following chart shows the circumstance of death as categorised by the Ombudsman for the 73 family and domestic violence fatalities received by the Office between 1 July 2012 and 30 June 2016.

| Circumstances of Death

|

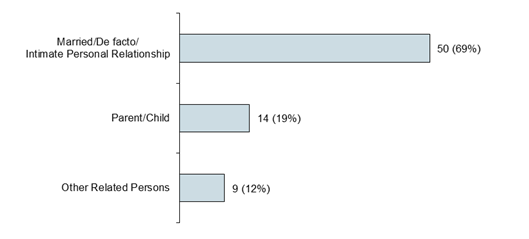

Family and domestic relationships

As shown in the following chart, married, de facto, or intimate personal relationship are the most common relationships involved in family and domestic violence fatalities.

| Family and Domestic Relationships

|

Of the 73 family and domestic violence fatalities received by the Office from 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2016:

- 50 fatalities (69%) involved a married, de facto or intimate personal relationship, of which there were 44 alleged homicides and six apparent suicides. The 50 fatalities included 10 deaths that occurred in five cases of alleged homicide/suicide and, in all five cases, a female was allegedly killed by a male, who subsequently died in circumstances of apparent suicide. The sixth apparent suicide involved a male. Of the remaining 39 alleged homicides, 25 (64%) of the people who died were female and 14 (36%) were male;

- There were 14 people who died (19%) who were either the parent or adult child of the suspected perpetrator. Of these, seven (50%) were female and seven (50%) were male. In 10 cases (71%) the person who died was the parent or step-parent and in four cases (29%) the person who died was the adult child or step-child; and

- There were nine people who died (12%) who were otherwise related to the suspected perpetrator (including siblings and extended family relationships). Of these, four (44%) were female and five (56%) were male.

Patterns, Trends and Case Studies Relating to Family and Domestic Violence Fatality Reviews

State policy and planning to reduce family and domestic violence fatalities

The State Strategy, released in 2012, sets out the State Government’s commitment to reducing family and domestic violence, identifying that it ‘builds on reforms already undertaken through the[WA Strategic Plan]…’ (page 3).

The DCPFS website Family and Domestic Violence Strategic Planning page (available at www.dcp.wa.gov.au) states DCPFS is the lead agency responsible for family and domestic violence strategic planning in Western Australia. This includes development, implementation and monitoring of the State Strategy and contribution to the National Plan. Strategic planning is overseen by the FDV Governance Council, comprising senior representatives from State and Commonwealth Government agencies and the Women’s Council for Domestic and Family Violence Services (WA), with input from the FDV Advisory Network.

The Ombudsman’s family and domestic violence fatality reviews and the Ombudsman’s own motion investigation and associated report, titled Investigation into issues associated with violence restraining orders and their relationship with family and domestic violence fatalities (the FDV investigation report), have identified that there is scope for State Government departments and authorities to improve the ways in which they respond to family and domestic violence. The Ombudsman has recommended that in the development of Action Plans under the State Strategy identify in more detail actions for achieving the State Strategy’s Primary State Outcomes, priorities among these actions, and allocation of responsibilities for these actions to specific State Government departments and authorities, as occurs with the National Plan. The findings and recommendations of the Law Reform Commission of Western Australia’s Enhancing Family and Domestic Violence Laws Final Report June 2014(available at www.lrc.justice.wa.gov.au) and of the Ombudsman’s FDV investigation report, could inform this work.

Type of relationships

The Ombudsman finalised 58 family and domestic violence fatality reviews from 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2016.

For 40 (69%) of the finalised reviews of family and domestic violence fatalities, the fatality occurred between persons who, either at the time of death or at some earlier time, had been involved in a married, de facto or other intimate personal relationship. For the remaining 18 (31%) of the finalised family and domestic violence fatality reviews, the fatality occurred between persons where the relationship was between a parent and their adult child or persons otherwise related (such as siblings and extended family relationships).

These two groups will be referred to as ‘intimate partner fatalities’ and ‘non‑intimate partner fatalities’.

For the 58 finalised reviews, the circumstances of the fatality were as follows:

- For the 40 intimate partner fatalities, 35 were alleged homicides and five were apparent suicides; and

- For the 18 non-intimate partner fatalities, all were alleged homicides.

Intimate partner relationships

Of the 35 intimate partner relationship fatalities involving alleged homicide:

- There were 24 fatalities where the person who died was female and the suspected perpetrator was male, 10 where the person who died was male and the suspected perpetrator was female, and one where the person who died was male and there were multiple suspected perpetrators of both genders;

- There were 16 fatalities that involved Aboriginal people as both the person who died and the suspected perpetrator. In nine of these fatalities the person who died was female and in seven the person who died was male;

- There were 19 fatalities that occurred at the joint residence of the person who died and the suspected perpetrator, five at the residence of the person who died or the residence of the suspected perpetrator, five at the residence of family or friends, and six at the workplace of the person who died or the suspected perpetrator or in a public place; and

- There were 18 fatalities that occurred in regional and remote areas, and in 14 of these the person who died was Aboriginal.

Non-intimate partner relationships

Of the 18 non-intimate partner fatalities, there were 12 fatalities involving a parent and adult child and six fatalities where the parties were otherwise related.

Of the 18 non-intimate partner fatalities, all of which involved alleged homicide:

- In eight fatalities the person who died was female and the suspected perpetrator was male. In the remaining 10 fatalities where the person who died was male, seven of the suspected perpetrators were male and three were female;

- There were five non-intimate partner fatalities that involved Aboriginal people as both the person who died and the suspected perpetrator;

- There were seven fatalities that occurred at the joint residence of the person who died and the suspected perpetrator, eight at the residence of the person who died or the residence of the suspected perpetrator, and three at the residence of family or friends or in a public place; and

- There were six fatalities that occurred in regional and remote areas.

Prior reports of family and domestic violence

Intimate partner fatalities were more likely than non-intimate partner fatalities to have involved previous reports of alleged family and domestic violence between the parties. In 23 (66%) of the 35 intimate partner fatalities involving alleged homicide finalised between 1 July 2012 and 30 June 2016, alleged family and domestic violence between the parties had been reported to WAPOL and/or to other public authorities. In six (33%) of the 18 non-intimate partner fatalities finalised between 1 July 2012 and 30 June 2016, alleged family and domestic violence between the parties had been reported to WAPOL and/or other public authorities.

Collation of data to build our understanding about communities who are over-represented in family and domestic violence

Principle 7 of the State Strategy states that:

An effective system will acknowledge that to achieve substantive equality, partnerships must be developed in consultation with specific communities of interest including people with a disability, people from diverse sexualities and/or gender, people from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds (page 5).

The Ombudsman’s FDV investigation report found that the research literature identifies that there are higher rates of family and domestic violence among certain communities in Western Australia. However, there are limitations to the supporting data, resulting in varying estimates of the numbers of people in these communities who experience family and domestic violence and a limited understanding of their experiences.

Of the 29 family and domestic violence fatalities where there had been prior reports of alleged family and domestic violence between the parties, from the records available:

- One fatality involved a deceased person with a disability;

- None of the fatalities involved a deceased person who identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans or intersex;

- Seventeen fatalities involved a deceased Aboriginal person; and

- Seventeen fatalities had occurred in regional/remote Western Australia.

Examination of the family and domestic violence fatality review data provides some insight into the issues relevant to these communities. However, these numbers are limited and greater insight is only possible through consideration of all reported family and domestic violence, not just where this results in a fatality. The Ombudsman’s FDV investigation report found that neither the State Strategy nor the Achievement Report to 2013 identify any actions to improve the collection of data relating to different communities experiencing higher rates of family and domestic violence, for example through the collection of cultural, demographic and socioeconomic data. The Ombudsman has recommended that in developing and implementing future phases of Western Australia’s Family and Domestic Violence Prevention Strategy to 2022: Creating Safer Communities, DCPFS collaborates with WAPOL, DOTAG and other relevant agencies to identify and incorporate actions to be taken by State Government departments and authorities to collect data about communities who are over-represented in family and domestic violence, to inform evidence-based strategies tailored to addressing family and domestic violence in these communities.

Identification of family and domestic violence incidents

Of the 29 family and domestic violence fatalities where there had been prior reports of alleged family and domestic violence between the parties, WAPOL was the agency to receive the majority of these reports. The Ombudsman’s FDV investigation report also noted that DCPFS may become aware of family and domestic violence through a referral to DCPFS and subsequent assessment through the duty interaction process. Identification of family and domestic violence is integral to the agency being in a position to implement its family and domestic violence policy and processes to address perpetrator accountability and promote victim safety and support. However, the Ombudsman’s reviews and own motion investigations have identified missed opportunities to identify family and domestic violence in interactions. In 2015-16, the Ombudsman has made recommendations that public authorities ensure all reported family and domestic violence is correctly identified.

Provision of agency support to obtain a violence restraining order

As identified above, WAPOL is likely to receive the majority of reports of family and domestic violence. WAPOL is not currently required by legislation or policy to provide victims with information and advice about violence restraining orders when attending the scene of acts of family and domestic violence. However, its attendance at the scene affords WAPOL with the opportunity to provide victims with information and advice about:

- What a violence restraining order is and how it can enhance their safety;

- How to apply for a violence restraining order; and

- What support services are available to provide further advice and assistance with obtaining a violence restraining order, and how to access these support services.

The Ombudsman’s FDV investigation report examined WAPOL’s response to FDV incidents through the review of 75 Domestic Violence Incident Reports (associated with 30 fatalities). The FDV investigation report found that WAPOL recorded the provision of information and advice about violence restraining orders in 19 of the 75 (25%) instances. The Ombudsman has recommended that WAPOL amends the Commissioner’s Operations and Procedures Manual to require that victims of family and domestic violence are provided with verbal information and advice about violence restraining orders in all reported instances of family and domestic violence. Further, the Ombudsman has recommended that WAPOL collaborates with DCPFS and DOTAG to develop an ‘aide memoire’ that sets out the key information and advice about violence restraining orders that WAPOL should provide to victims of all reported instances of family and domestic violence, and that this ‘aide memoire’ is also developed in consultation with Aboriginal people to ensure its appropriateness for family violence incidents involving Aboriginal people.

The Ombudsman’s FDV investigation report also examined the response by DCPFS to prior reports of family and domestic violence involving 30 children who experienced family and domestic violence associated with the 30 fatalities. The FDV investigation report found that DCPFS did not provide any active referrals for legal advice or help from an appropriate service to obtain a violence restraining order for any of the children involved in the 30 fatalities. The Ombudsman has recommended that DCPFS complies with the requirements of its Family and Domestic Violence Practice Guidance, in particular, that:

[w]here a violence restraining order is considered desirable or necessary but a decision is made for the Department not to apply for the order, the non‑abusive adult victim should be given an active referral for legal advice and help from an appropriate service.

Further, the Ombudsman’s FDV investigation report has noted DCPFS’s Family and Domestic Violence Practice Guidance also identifies that taking out a violence restraining order on behalf of a child ‘can assist in the protection of that child without the need for removal (intervention action) from his or her family home’, and can serve to assist adult victims of violence when it would decrease risk to the adult victim if the Department was the applicant. The Ombudsman has made three recommendations relating to DCPFS’s improved compliance with the provisions of its Family and Domestic Violence Practice Guidance in seeking violence restraining orders on behalf of children, including that in its implementation of section 18(2) of the Restraining Orders Act 1997, DCPFS complies with its Family and Domestic Violence Practice Guidance which identifies that DCPFS officers should consider seeking a violence restraining order on behalf of a child if the violence is likely to escalate and the children are at risk of further abuse, and/or it would decrease risk to the adult victim if the Department was the applicant for the violence restraining order.

The Ombudsman’s FDV investigation report also identified the importance of opportunities for victims to seek help and for perpetrators to be held to account at other points in the process for obtaining a violence restraining order, and that these opportunities are acted upon, not just by WAPOL but by all State Government departments and authorities. The Ombudsman has recommended that in developing and implementing future phases of Western Australia’s Family and Domestic Violence Prevention Strategy to 2022: Creating Safer Communities, DCPFS specifically identifies and incorporates opportunities for State Government departments and authorities to deliver information and advice about violence restraining orders, beyond the initial response by WAPOL.

The Ombudsman’s FDV investigation report examined a sample of 41,229 hearings regarding violence restraining orders and identified that an application for a violence restraining order was dismissed or not granted as an outcome of 6,988 hearings (17%) in the investigation period. In cases where an application for a violence restraining order has been dismissed it may still be appropriate to provide safety planning assistance. The Ombudsman has recommended that DOTAG, in collaboration with DCPFS, identifies and incorporates into Western Australia’s Family and Domestic Violence Prevention Strategy to 2022: Creating Safer Communities, ways of ensuring that, in cases where an application for a violence restraining order has been dismissed, if appropriate, victims are provided with referrals to appropriate safety planning assistance.

Provision of support to victims experiencing family and domestic violence

In November 2015, DCPFS launched the Western Australia Family and Domestic Violence Common Risk Assessment and Risk Management Framework (Second edition) (available at www.dcp.wa.gov.au). This across government framework states that:

The purpose of risk assessment is to determine the risk and safety for the adult victim and children, taking into consideration the range of victim and perpetrator risk factors that affect the likelihood and severity of future violence.

Risk assessment must be undertaken when family and domestic violence has been identified…

Risk assessment is conducted for a number of reasons including:

- evaluating the risk of re-assault for a victim;

- evaluating the risk of homicide;

- informing service system and justice responses;

- supporting women to understand their own level of risk and the risk to children and/or to validate a woman’s own assessment of her level of safety; and

- establishing a basis from which a case can be monitored (pages 36-37).

The Ombudsman’s reviews and FDV investigation report have noted that, where agencies become aware of family and domestic violence, they do not always undertake a comprehensive assessment of the associated risk of harm and provide support and safety planning.

In 2015-16, the Ombudsman has made recommendations to public authorities that they ensure compliance with their family and domestic violence policy requirements, including assessing risk of future harm and providing support to address the impact of experiencing family and domestic violence.

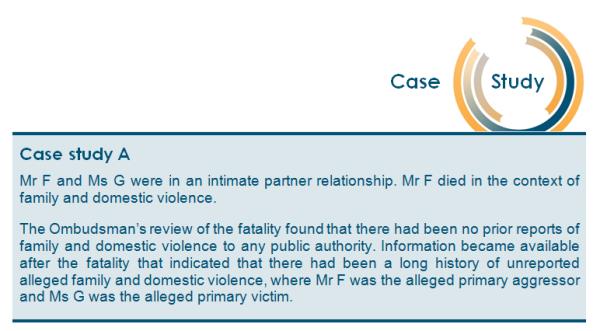

Fatalities with no prior reported family and domestic violence

In 12 (34%) of the 35 intimate partner fatalities involving alleged homicide finalised between 1 July 2012 and 30 June 2016, the fatal incident was the only family and domestic violence between the parties that had been reported, on the information available to the Office, to WAPOL and/or other public authorities. It is important to note, however, research indicating under‑reporting of family and domestic violence. The Australian Bureau of Statistics’ Personal Safety Survey 2012 ‘collected information about a person's help seeking behaviours in relation to their experience of partner violence’.

For example, this research found that:

An estimated 190,100 women (80% of the 237,100 women who had experienced current partner violence) had never contacted the police about the violence by their current partner [Original emphasis].

The Ombudsman’s reviews provide information on family and domestic violence fatalities where there is no previous reported history of family and domestic violence, including cases where information becomes available after the death to confirm a history of unreported family and domestic violence, as shown in the following case study.

The Ombudsman will continue to collate information on family and domestic violence fatalities where there is no reported history of family and domestic violence, to identify patterns and trends and consider improvements that may increase reporting of family and domestic violence and access to supports.

Family violence involving Aboriginal people

Of the 58 family and domestic violence fatality reviews finalised from 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2016, Aboriginal Western Australians were over-represented, with 21 persons who died being Aboriginal. In each case, the suspected perpetrator was also Aboriginal. There were 17 of these fatalities that occurred in a regional or remote area of Western Australia, of which 14 were intimate partner fatalities.

The Ombudsman’s reviews and FDV investigation report identify the over-representation of Aboriginal people in family and domestic violence fatalities. This is consistent with the research literature that Aboriginal people are ‘more likely to be victims of violence than any other section of Australian society’ (Cripps, K and Davis, M, Communities working to reduce Indigenous family violence, Brief 12, June 2012, Indigenous Justice Clearinghouse, New South Wales, 2012, p. 1) and that Aboriginal people experience family and domestic violence at ‘significantly higher rates than other Australians.’ (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, Ending family violence and abuse in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities – Key Issues, An overview paper of research and findings by the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, 2001 - 2006, Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, June 2006, p. 6).

As discussed in the Ombudsman’s FDV investigation report, the research literature suggests that there are a number of contextual factors contributing to the prevalence and seriousness of family violence in Aboriginal communities and that:

…violence against women within the Indigenous Australian communities need[s] to be understood within the specific historical and cultural context of colonisation and systemic disadvantage. Any discussion of violence in contemporary Indigenous communities must be located within this historical context. Similarly, any discussion of “causes” of violence within the community must recognise and reflect the impact of colonialism and the indelible impact of violence perpetrated by white colonialists against Indigenous peoples…A meta-evaluation of literature…identified many “causes” of family violence in Indigenous Australian communities, including historical factors such as: collective dispossession; the loss of land and traditional culture; the fragmentation of kinship systems and Aboriginal law; poverty and unemployment; structural racism; drug and alcohol misuse; institutionalisation; and the decline of traditional Aboriginal men’s role and status - while “powerless” in relation to mainstream society, Indigenous men may seek compensation by exerting power over women and children...(Blagg, H, Bluett-Boyd, N, and Williams, E, Innovative models in addressing violence against Indigenous women: State of knowledge paper, Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety Limited, Sydney, New South Wales, August 2015, p. 3).

The Ombudsman’s FDV investigation report notes that, in addition to the challenges faced by all victims in reporting family and domestic violence, the research literature identifies additional disincentives to reporting family and domestic violence faced by Aboriginal people:

Indigenous women continuously balance off the desire to stop the violence by reporting to the police with the potential consequences for themselves and other family members that may result from approaching the police; often concluding that the negatives outweigh the positives. Synthesizing the literature on the topic reveals a number of consistent themes, including: a reluctance to report because of fear of the police, the perpetrator and perpetrator’s kin; fear of “payback” by the offender’s family if he is jailed; concerns the offender might become “a death in custody”; a cultural reluctance to become involved with non-Indigenous justice systems, particularly a system viewed as an instrument of dispossession by many people in the Indigenous community; a degree of normalisation of violence in some families and a degree of fatalism about change; the impact of “lateral violence” … which makes victims subject to intimidation and community denunciation for reporting offenders, in Indigenous communities; negative experiences of contact with the police when previously attempting to report violence (such as being arrested on outstanding warrants); fears that their children will be removed if they are seen as being part of an abusive house-hold; lack of transport on rural and remote communities; and a general lack of culturally secure services (Blagg, H, Bluett-Boyd, N and Williams, E, Innovative models in addressing violence against Indigenous women: State of knowledge paper, Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety Limited, Sydney, New South Wales, August 2015, p. 13).

The Ombudsman’s reviews and FDV investigation report have identified that Aboriginal victims want the violence to end, but not necessarily always through the use of violence restraining orders.

A separate strategy to prevent and reduce Aboriginal family violence

In examining the family and domestic violence fatalities involving Aboriginal people, the research literature and stakeholder perspectives, the FDV investigation report identified a gap in that there is no strategy solely aimed at addressing family violence experienced by Aboriginal people and in Aboriginal communities.

The findings of the Ombudsman’s FDV investigation report strongly support the development of a separate strategy (linked to the State Strategy and consistent with, and supported by, the State Strategy) that is specifically tailored to preventing and reducing Aboriginal family violence. This can be summarised as three key points.

Firstly, the findings set out in Chapters 4 and 5 of the FDV investigation report identify that Aboriginal people are over-represented, both as victims of family and domestic violence and victims of fatalities arising from this violence.

Secondly, the research literature, discussed in Chapter 6 of the FDV investigation report suggests a distinctive ‘…nature, history and context of family violence in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.’ (National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Women’s Alliance, Submission to the Finance and Public Administration Committee Inquiry into Domestic Violence in Australia, National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Women’s Alliance, New South Wales, 31 July 2014, p. 5). The research literature further suggests that combating violence is likely to require approaches that are informed by and respond to this experience of family violence.

Thirdly, the findings set out in the FDV investigation report demonstrate how the unique factors associated with Aboriginal family violence have resulted in important aspects of the use of violence restraining orders by Aboriginal people which are different from those of non‑Aboriginal people.

The Ombudsman recommended that DCPFS, as the lead agency responsible for family and domestic violence strategic planning in Western Australia, develops a strategy that is specifically tailored to preventing and reducing Aboriginal family violence, and is linked to, consistent with, and supported by Western Australia’s Family and Domestic Violence Prevention Strategy to 2022: Creating Safer Communities. The FDV investigation report identified that development of the strategy must include and encourage the involvement of Aboriginal people in a full and active way, at each stage and level of the development of the strategy, and be comprehensively informed by Aboriginal culture. Doing so would mean that an Aboriginal family violence strategy would be developed with, and by, Aboriginal people. The Ombudsman has recommended that DCPFS, in developing a strategy tailored to preventing and reducing Aboriginal family violence, actively invites and encourages the involvement of Aboriginal people in a full and active way at each stage and level of the process, and be comprehensively informed by Aboriginal culture.

Limited use of violence restraining orders

The FDV investigation report identified that while Aboriginal people are significantly over-represented as victims of family and domestic violence, they are less likely than non-Aboriginal people to seek a violence restraining order. The FDV investigation report examined the research literature and views of stakeholders on the possible reasons for this lower use of violence restraining orders by Aboriginal people, identifying that the process for obtaining a violence restraining order is not necessarily always culturally appropriate for Aboriginal victims and that Aboriginal people in regional and remote locations face additional logistical and structural barriers in the process of obtaining a violence restraining order. The Ombudsman has recommended that DOTAG, in collaboration with key stakeholders, considers opportunities to address the cultural, logistical and structural barriers to Aboriginal victims seeking a violence restraining order, and ensures that Aboriginal people are involved in a full and active way at each stage and level of this process, and that this process is comprehensively informed by Aboriginal culture.

The FDV investigation report noted that data examined by the Office concerning the use of police orders and violence restraining orders by Aboriginal people in Western Australia indicates that Aboriginal victims are more likely to be protected by a police order than a violence restraining order. This data is consistent with information examined in the Ombudsman’s reviews of family and domestic violence fatalities involving Aboriginal people. The Ombudsman has made a number of recommendations, set out in the FDV investigation report, to improve the use of violence restraining orders to prevent or reduce family and domestic violence fatalities, including that DCPFS considers the findings of the Ombudsman’s investigation regarding the link between the use of police orders and violence restraining orders by Aboriginal people in developing and implementing the Aboriginal family violence strategy.

Strategies to recognise and address the co-occurrence of alcohol consumption and Aboriginal family violence

The Ombudsman’s reviews of the family and domestic violence fatalities of Aboriginal people and prior reported family violence between the parties, identify a high co-occurrence of alcohol consumption and family violence. The FDV investigation report examined the research literature on the relationship between alcohol use and family and domestic violence and found that the research literature regularly identifies alcohol as ‘a significant risk factor associated with intimate partner and family violence in Aboriginal communities’. (Mitchell, L, Domestic violence in Australia – an overview of the issues, Parliament of Australia, 2011, Canberra, accessed 16 October 2014, pp. 6-7). As with family and domestic violence in non-Aboriginal communities, the research literature suggests that ‘while alcohol consumption [is] a common contributing factor … it should be viewed as an important situational factor that exacerbates the seriousness of conflict, rather than a cause of violence’. (Buzawa, E, Buzawa, C and Stark, E, Responding to Domestic Violence, Sage Publications, 4th Edition, 2012, Los Angeles, p. 99; Morgan, A. and McAtamney, A. ‘Key issues in alcohol-related violence,’ Australian Institute of Criminology, Canberra, 2009, viewed 27 March 2015, p. 3). The Ombudsman has recommended that DCPFS, in developing the Aboriginal family violence strategy referred to at Recommendation 4, incorporates strategies that recognise and address the co‑occurrence of alcohol use and Aboriginal family violence.

Strategies to address the over-representation of family violence involving Aboriginal people in regional WA

Of the 21 family and domestic violence fatality reviews finalised from 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2016 involving Aboriginal people, 17 of these fatalities occurred in a regional or remote area of Western Australia. Ten of these fatalities occurred in the Kimberley region, which is home to 1.6 per cent of people in the Western Australian population.

Building on the work of the State Strategy,the Freedom from Fear: Working towards the elimination of family and domestic violence in Western Australia Action Plan 2015 was launched in September 2015. ThisAction Planincludes the priority to ‘Target communities and populations at greatest risk’ and ‘Develop and implement a plan for the Kimberley region’ identifying that:

In comparison to other regional and metropolitan locations in Western Australia the Kimberley region has the highest rates, per head of population, of reported family and domestic violence and hospitalisations for domestic assault... (page 10).

In identifying the Kimberley as a region of priority for an improved response to family and domestic violence, Safer Families, Safer Communities Kimberley Family Violence Regional Plan 2015-2020 (the Kimberley Plan) (available at www.dcp.wa.gov.au) was launched in October 2015. The Kimberley Plan aims to:

…increase the health, safety and wellbeing of women, children and men living in the Kimberley region by working towards a reduction in family violence. The Kimberley Plan which sets out a framework for responding to family violence, includes strategies that will benefit all members of the Kimberley community as well as priority areas targeted at responding to Aboriginal family violence (page 4).

… This will be achieved through a whole of community approach that promotes:

- shared responsibility for the safety and wellbeing of children, individuals and families;

- developing culture and community based responses to family violence;

- building strong and safe communities; and

- developing services and a service system that is integrated, culturally secure, client centered, accessible and effective (page 10).

The Ombudsman has recommended that DCPFS, as the lead agency responsible for family and domestic violence strategic planning in Western Australia, develops a strategy that is specifically tailored to preventing and reducing Aboriginal family violence, and is linked to, consistent with, and supported by Western Australia’s Family and Domestic Violence Prevention Strategy to 2022: Creating Safer Communities that would encompass all regions of Western Australia.

Factors co-occurring with family and domestic violence

Where family and domestic violence co-occurs with alcohol use, drug use and/or mental health issues, a collaborative, across service approach is needed. Treatment services may not always identify the risk of family and domestic violence and provide an appropriate response.

Co-occurrence with alcohol and other drug use

Consistent with the research literature discussed relating to the co-occurrence between alcohol consumption and/or drug use and incidents of family and domestic violence (as outlined in the Ombudsman’s FDV investigation report), the National Plan (available at www.dss.gov.au) observes that:

Alcohol is usually seen as a trigger, or a feature, of violence against women and their children rather than a cause. Research shows that addressing alcohol in isolation will not automatically reduce violence against women and their children. This is because alcohol does not, of itself, create the underlying attitudes that lead to controlling or violent behaviour (page 29).

The National Plan and the National Drug Strategy 2010-2015 identify initiatives to address alcohol and drug use, and the co-occurrence with family and domestic violence. The Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education’s National framework for action to prevent alcohol-related family violence (available at www.fare.org.au/preventalcfv/) states:

Integrated and coordinated service models within the AOD [alcohol and other drug] and family violence sectors in Australia are rare. Historically, the sectors have worked independently of each other despite the long-recognised association between alcohol and family violence. Part of the reason is that models of treatment for alcohol use disorders have traditionally been focused towards the needs of individuals and in particular, men (page 36).

On the information available, relating to the 53 family and domestic violence fatalities involving alleged homicide that were finalised from 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2016, the Ombudsman’s reviews identify where alcohol use and/or drug use are factors associated with the fatality, and where there may be a history of alcohol use and/or drug use.

|

ALCOHOL USE |

DRUG USE |

||

Associated with fatal event |

Prior history |

Associated with fatal event |

Prior history |

|

Person who died only |

1 |

0 |

2 |

5 |

Suspected perpetrator only |

3 |

13 |

7 |

10 |

Both person who died and suspected perpetrator |

19 |

19 |

3 |

6 |

Total |

23 |

32 |

12 |

21 |

The Ombudsman’s reviews and FDV investigation report have identified that in Western Australia, the State Strategy does not mention or address alcohol and its relationship with family and domestic violence. However, the goal of the Drug and Alcohol Office’s Drug and Alcohol Interagency Strategic Framework for Western Australia 2011-2015 (the Framework) is to ‘prevent and reduce the adverse impacts of alcohol and other drugs in the Western Australian community’ (page 5).

As one of these adverse impacts, the Framework highlights ‘violence and family and relationship breakdown’ as a result of ‘problematic drug and alcohol use’ (page 94). Stakeholders have suggested to the Ombudsman that programs and services for victims and perpetrators of violence in Western Australia, including family and domestic violence, do not address its co-occurrence with alcohol and other drug abuse. Specifically, this means that programs and services addressing family and domestic violence:

- May deny victims or perpetrators access to their services, particularly if they are under the influence of alcohol and other drugs; and

- Frequently do not address victims’ or perpetrators’ alcohol and other drug abuse issues.

Conversely, stakeholders have suggested programs and services which focus on alcohol and other drug use generally do not necessarily:

- Address perpetrators’ violent behaviour; or

- Respond to the needs of victims resulting from their experience of family and domestic violence.

The concerns of stakeholders are consistent with the research literature as outlined in the Ombudsman’s FDV investigation report. Given the level of recorded alcohol use associated with the Ombudsman’s reviews, the Ombudsman has recommended that DCPFS and the Mental Health Commission collaborate to include initiatives in Action Plans under the State Strategy which recognise and address the co-occurrence of alcohol use and family and domestic violence.

Co-occurrence of mental health issues

As with alcohol and drug use, it is noted that the State Strategy does not mention mental health issues and the relationship with family and domestic violence. Though it is noted that in screening for family and domestic violence, the Western Australia Family and Domestic Violence Common Risk Assessment and Risk Management Framework (second edition) (available at www.dcp.wa.gov.au) states that:

Perpetrators often present with issues that coexist with their use of violence, for example, alcohol and drug misuse or mental health concerns. These coexisting issues are not to be blamed for the violence, but they may exacerbate the violence or act as a barrier to accessing the service system or making behavioural change.

The primary focus of referral for perpetrators of family and domestic violence should be the violence itself. Coexisting issues may be addressed simultaneously, where appropriate (page 53, our emphasis).

and

Family and domestic violence may be present, but undisclosed when a woman presents at a service for assistance with other issues such as health concerns, financial crisis, legal difficulties, parenting problems, mental health concerns, drug and/or alcohol misuse or homelessness (page 29, our emphasis).

The DCPFS’s Western Australia Family and Domestic Violence Common Risk Assessment and Risk Management Framework identifies mental health as a potential risk factor for family and domestic violence, and indicates that screening should be undertaken by mental health services (page 29).

On the information available, relating to the 53 family and domestic violence fatalities involving alleged homicide that were finalised from 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2016, the Ombudsman’s reviews identify where mental health is potentially associated with the fatality, and where there may be a history of a mental health diagnosis.

Issues identified in Family and Domestic Violence Fatality Reviews

It is important to note that:

|

The following are the types of issues identified when undertaking family and domestic violence fatality reviews.

|

Recommendations

In response to the issues identified, the Ombudsman makes recommendations to prevent or reduce family and domestic violence fatalities. The following recommendations were made by the Ombudsman in 2015-16 arising from family and domestic violence fatality reviews (certain recommendations may be de-identified to ensure confidentiality).

|

The Ombudsman will actively monitor what steps have been taken to give effect to these recommendations. The results of this monitoring will be reported in the 2016-17 Annual Report. |

Timely handling of notifications and reviews

The Office places a strong emphasis on the timely review of family and domestic violence fatalities. This ensures reviews contribute, in the most timely way possible, to the prevention or reduction of future deaths. In 2015-16, timely review processes have resulted in one third of reviews being completed within three months and 80% of reviews completed within 12 months.

Major own motion investigations arising from family and domestic violence fatality reviews

In addition to investigations of individual family and domestic violence fatalities, the Office identifies patterns and trends arising out of reviews to inform major own motion investigations that examine the practice of public authorities that provide services to children, their families and their communities.

Major own motion investigations arising from family and domestic violence fatality reviews

In addition to investigations of individual family and domestic violence fatalities, the Office identifies patterns and trends arising out of reviews to inform major own motion investigations that examine the practice of public authorities that provide services to children, their families and their communities.

Investigation into issues associated with violence restraining orders and their relationship with family and domestic violence fatalities

Investigation into issues associated with violence restraining orders and their relationship with family and domestic violence fatalities

In November 2015, the Ombudsman tabled in Parliament a report of a major own motion investigation entitled Investigation into issues associated with violence restraining orders and their relationship with family and domestic violence fatalities. The reportis availableon the Ombudsman’s website.

About the investigation

Through the review of family and domestic violence fatalities, the Ombudsman identified a pattern of cases in which violence restraining orders were, or had been, in place between the person who was killed and the suspected perpetrator, or between the person who was killed or the suspected perpetrator and other parties. The Ombudsman also identified a pattern of cases in which violence restraining orders were not used, although family and domestic violence had been, or had been recorded as, occurring and State Government departments and authorities had been contacted.

Accordingly, the Ombudsman decided to undertake an investigation into issues associated with violence restraining orders and their relationship with family and domestic violence fatalities, with a view to determining whether it may be appropriate to make recommendations to any State Government department or authority about ways to prevent or reduce family and domestic violence fatalities.

The investigation had two aims. Firstly, arising from the work of the Ombudsman in reviewing family and domestic violence fatalities, the investigation aimed to set out a comprehensive understanding of family and domestic violence in Western Australia. Secondly, informed by this comprehensive understanding, the investigation aimed to examine the actions of State Government departments and authorities in administering their relevant legislative responsibilities, including particularly the Restraining Orders Act 1997, with a focus on violence restraining orders.

Throughout the investigation, the Office also considered if, and if so how, family and domestic violence affects different people and groups of people, in particular Aboriginal people (given the significant over-representation of Aboriginal Western Australians in family and domestic violence fatalities).

Methodology

- The Office examined 30 family and domestic violence fatalities (the 30 fatalities) notified to the Ombudsman over a defined 18 month period (the investigation period).

- The Office also collected and analysed a comprehensive set of

de-identified state-wide data for the investigation period (the state-wide data), regarding:

- All family and domestic violence incidents attended, and all violence restraining orders served, by WAPOL;

- All applications for violence restraining orders lodged in, and all violence restraining orders issued by, the Magistrates Court and the Children’s Court; and

- All court hearings and outcomes for charges relating to breaches of violence restraining orders.

- The investigation also included an extensive literature review and stakeholder engagement.

Key findings: Family and domestic violence in Western Australia

- In the investigation period, WAPOL reported that they responded to 1,055,414 calls for assistance from the public and that 688,998 of these calls required police to attend to provide assistance.

- Of the 688,998 incidents attended by WAPOL, 75,983 incidents (11%) were recorded by WAPOL as family and domestic violence incidents.

- In 20,480 of these 75,983 incidents, an offence against the person was detected. For these 20,480 incidents, the Office found that:

- 12,962 of these incidents occurred in Metropolitan Police Districts

(63%) and 7,518 in Regional Police Districts (37%); and- Despite having the lowest population of all of the regions in Western Australia, the Kimberley Police District had the third highest number of domestic violence incidents (and domestic violence offences).

- At the 20,480 incidents, police officers detected a total of 26,023 offences against the person.

- WAPOL recorded 24,479 victims for these 26,023 offences.

- Of the 24,479 victims:

- 17,539 (72%) were recorded as being female; and

- 8,150 (33%) were recorded as being Indigenous.

Key findings: Family and domestic fatalities notified to the Ombudsman

During the investigation period, WAPOL notified the Ombudsman of 30 family and domestic violence fatalities.

The Office’s analysis of the 30 fatalities identified that:

- 15 (50%) of the 30 people who were killed were Aboriginal;

- 15 (50%) of the 30 people who were killed were residing in a regional, remote, or very remote region of Western Australia, with remote and very remote regions significantly over-represented;

- In 16 fatalities (53%), there was a recorded prior history of family and domestic violence involving the person who was killed and the suspected perpetrator;

- In 17 of the 30 fatalities (57%), violence restraining orders involving at least one of the people involved in the fatality were granted at some point in time (a total of 48 violence restraining orders);

- The average age of the people who were killed was 36 years, with over a third between 35 and 44;

- 14 of the 30 suspected perpetrators (47%) had been held in custody for criminal offences at some point prior to the time when a person was killed and 18 (60%) had contact with the justice system; and

- In 19 of the 30 fatalities (63%) the records of State Government departments and authorities and the courts indicated that alcohol and/or other drugs had been used by the perpetrator immediately prior to the fatal incident.

Key findings: Key principles for administering the Restraining Orders Act 1997

The investigation identified nine key principles for State Government departments and authorities to apply when responding to family and domestic violence and administering the Restraining Orders Act 1997. Applying these principles will enable State Government departments and authorities to have the greatest impact on preventing and reducing family and domestic violence and related fatalities:

i. Perpetrators use family and domestic violence to exercise power and control over victims;

ii. Victims of family and domestic violence will resist the violence and try to protect themselves;

iii. Victims may seek help to resist the violence and protect themselves, including help from State Government departments and authorities;

iv. When victims seek help, positive and consistent responses by State Government departments and authorities can prevent and reduce further violence;

v. Victims’ decisions about how they will resist violence and protect themselves may not always align with the expectations of State Government departments and authorities; this does not mean that victims do not need, want, or are less deserving of, help;

vi. Perpetrators of family and domestic violence make a decision to behave violently towards their victims;

vii. Perpetrators avoid taking responsibility for their behaviour and being held accountable for this behaviour by others;

viii. By responding decisively and holding perpetrators accountable for their behaviour, State Government departments and authorities can prevent and reduce further violence; and

ix. Perpetrators may seek to manipulate State Government departments and authorities, in order to maintain power and control over their victims and avoid being held accountable; State Government departments and authorities need to be alert to this.

Key findings: WAPOL’s initial response to reports of family and domestic violence

- In the 16 fatalities where WAPOL recorded a history of family and domestic violence between the person who was killed and the suspected perpetrator, WAPOL recorded 133 family and domestic violence incidents.

- WAPOL complied with requirements to attend the scene in

96 per cent of incidents. - A Domestic Violence Incident Report (DVIR) was submitted for 87 (65%) of the 133 family and domestic violence incidents between the person who was killed and the suspected perpetrator. For the remaining 46, a general incident report or Computer Aided Dispatch system recording was made.

- 75 DVIRs were submitted relating to these 87 recorded incidents (the 75 DVIRs).

Key findings: Providing advice and assistance and sharing information regarding violence restraining orders

- For the 30 fatalities it was recorded that:

- WAPOL provided information and advice about violence restraining orders, and sought consent to share information with support services, in a quarter of instances where WAPOL investigated a report of family and domestic violence relating to the 30 fatalities (19 of 75 DVIRs).

- WAPOL did not make any applications for violence restraining orders on behalf of the person who was killed or the suspected perpetrator in the 30 fatalities.

- There were 22 instances (31%) in which WAPOL issued a police order (of the 71 applicable DVIRs).

- In 56% of incidents related to the 30 fatalities no order was made or sought and a written reason was provided.

- In 77% of instances where ‘no consent and no safety concerns’ were recorded as the reason, this was inconsistent with other information recorded at the scene.

- The number of police orders issued has increased from 10,312 in

2009-10 to 17,761 in 2013-14.

Key findings: Applying for a violence restraining order

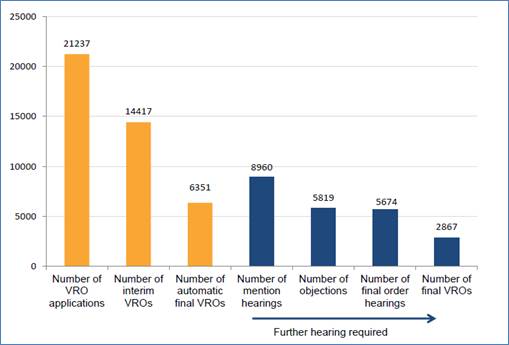

- In the investigation period, 21,237 applications for a violence restraining order were made in Western Australia.

- In 12,393 (58%) of these applications, the applicant identified that the person seeking to be protected was in a family and domestic relationship with the respondent. Of these 12,393 applications:

- 9,533 (77%) persons seeking to be protected were female;

- 8,620 (70%) applicants identified that the person seeking to be protected was, or had been, in an intimate partner relationship with the respondent; and

- 1,340 (11%) persons seeking to be protected identified themselves as Aboriginal or Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander.

Key findings: Aboriginal family violence

- Aboriginal Western Australians are significantly over-represented as victims of family violence, yet under-represented in the use of violence restraining orders. More particularly:

- 33% of all victims of domestic violence offences against the person were recorded by WAPOL as being Aboriginal;

- Half of the people who were killed in the 30 fatalities were Aboriginal; and

- 11% of all persons seeking to be protected by a violence restraining order, who were in a family and domestic relationship with the respondent identified themselves as Aboriginal or Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander.

Key findings: Obtaining a violence restraining order

- Applications for an interim violence restraining order frequently did not progress to a final violence restraining order in the investigation period:

- 14,417 interim violence restraining orders were made by the courts;

- 6,351 interim violence restraining orders automatically became final violence restraining orders without returning to court; and

- A final violence restraining order was granted as an outcome of 2,867 hearings.

- Considered collectively, this indicates that a total of approximately 43% of all applications for violence restraining orders go on to become final orders.

Source: Ombudsman Western Australia

Key findings: Serving violence restraining orders

- The Office identified that, in the investigation period, 13,378 violence restraining orders were served.

- 13,014 of these violence restraining orders were served personally, with 12,032 (92%) served personally by police officers.

Comparison of time taken to serve violence restraining orders

Ombudsman’s finding for the investigation period |

Office of the Auditor General’s finding (using data for the period |

|

Percentage of all violence restraining orders issued that were served within 4 days |

42% |

58% |

Average time to serve all violence restraining orders issued |

29 days |

44 days |

Average time to serve, without including outliers |

14 days |

18 days |

Source: Ombudsman Western Australia and Office of the Auditor General

Note: The Auditor General noted that ‘the average is impacted by a minority of orders where there is significant delay in service. A clearer estimate of service timeliness may be gained by looking only at orders served in 100 days’ or less. To enable this comparison, the Office has also excluded orders served on day 101 or after.

- The Office also identified that 6,300 violence restraining orders were served by WAPOL more than five days after the violence restraining order was granted.

- The Office modelled the implementation of the Law Reform Commission’s recommendation that, ‘if a family and domestic violence protection order has not been served on the person bound within 72 hours, [WAPOL] are to apply to a registrar of the court within 24 hours’.

- If this had been applicable during the investigation period, WAPOL would have been required to apply for oral service for 63 per cent of served violence restraining orders, resulting in 8,450 applications to do so to the registrar of the court.

Key findings: Responding to breaches of violence restraining orders

- During the investigation period, there were 8,767 alleged breaches of violence restraining orders reported to, and recorded by, WAPOL, with 3,753 alleged offenders recorded.

- During the investigation period, 3,099 of the 3,753 (83%) alleged offenders were charged with the offence of ‘breach of violence restraining order’.

- Of the 3,099 alleged offenders who were charged:

- 2,481 (80%) were arrested;

- 581 (19%) were summonsed to appear in court; and

- A warrant was issued for the remaining 37 (1%) alleged offenders.

- WAPOL arrested and charged 75 per cent of people alleged to have breached a violence restraining order in the 75 DVIRs relating to the 30 fatalities.

- In the investigation period, the Magistrates and Children’s Courts held 11,352 hearings relating to 8,147 charges of breach of a violence restraining order, and 2,676 alleged offenders.

- Of the 8,147 charges, 6,087 were finalised during the investigation period. The alleged offender was found guilty and a sentence imposed in 5,519 (91%) of the 6,087 finalised charges.

- The most frequent sentence imposed for breaching a violence restraining order was a fine (ranging from $10 to $3000), with 6,004 fines issued (64% of 9,378 sentencing outcomes). The second most frequent was imprisonment (879 occasions).

- Violence restraining orders are more likely to be breached, and less likely to be effective in high risk cases.

- Several factors increase the risk of a violence restraining order being breached, including separation, history of violence or crime by the perpetrator, or

non-compliance with court conditions by a perpetrator. - In the 30 fatalities:

- 8 people who were killed in the 30 fatalities intended to separate, or had recently separated, from the suspected perpetrator;

- 18 of the 30 suspected perpetrators had contact with the justice system at some point prior to the time when a person was killed; and

- WAPOL recorded a suspected perpetrator as being in breach of an order or other protective conditions imposed by the court in 17 per cent of the 75 DVIRs relating to the 30 fatalities.

- The Office’s analysis identified that, in high risk cases, violence restraining orders may be insufficient if used alone and additional strategies may be useful.

- One such additional strategy is the consideration of deferral of bail or, in high risk cases in certain circumstances, a presumption against bail.

Key findings: Investigating if an act of family and domestic violence is a criminal offence

- Violence restraining orders are not a substitute for criminal charges where an offence has been committed.

- WAPOL’s policy, in its Commissioner’s Operations and Procedures (COPS) Manual ‘is pro-charge, pro-arrest and pro-prosecution; where evidence exists that a criminal offence has been committed’ (DV 1.1.2).

- The Office’s examination of the 75 DVIRs found that:

- WAPOL detected an offence in 51 of the 75 DVIRs (68%);

- An offender was processed (arrested or summonsed) on 29 of these 51 occasions (57%); and

- The victim was most likely to be interviewed (92%), followed by the suspect/person of interest (73%), with other significant witnesses least likely to be interviewed (48% of 46 incidents where potential significant witnesses were recorded).

Key findings: The use of violence restraining orders to protect children from family and domestic violence

- Research identifies that family and domestic violence causes harm to children.

- The Office identified that there were 30 children (aged less than 18 years) who experienced family and domestic violence associated with the 30 fatalities.

- Of these 30 children:

- 18 (60%) were male and 12 were female; and

- 21 (70%) were Aboriginal and nine were non-Aboriginal.

- The Office also identified children regarding whom the state-wide data indicated that:

- A violence restraining order was applied for in the Magistrates Court in the investigation period;

- The grounds selected by the applicant in applying for a violence restraining order included ‘exposing a child to an act of family and domestic violence’; and