Complaint Resolution

A core function of the Ombudsman is to resolve complaints received from the public about the decision making and practices of State Government agencies, local governments and universities (commonly referred to as public authorities). This section of the report provides information about how the Office assists the public by providing independent and timely complaint resolution and investigation services or, where appropriate, referring them to a more appropriate body to handle the issues they have raised.

Contacts

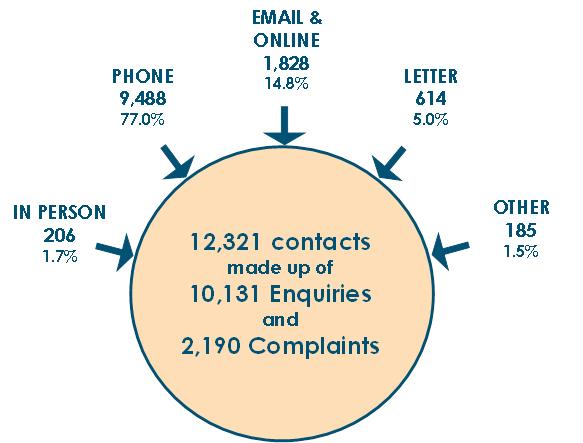

In 2016-17, the Office received 12,321 contacts from members of the public consisting of:

- 10,131 enquiries from people seeking advice about an issue or information on how to make a complaint; and

- 2,190 written complaints from people seeking assistance to resolve their concerns about the decision making and administrative practices of a range of public authorities.

Enquiries Received

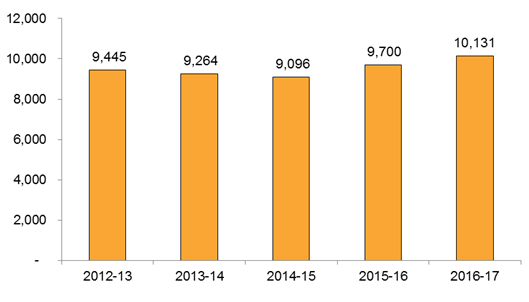

There were 10,131 enquiries received during the year.

For enquiries about matters that are within the Ombudsman’s jurisdiction, staff provide information about the role of the Office and how to make a complaint. For approximately half of these enquiries, the enquirer is referred back to the public authority in the first instance to give it the opportunity to hear about and deal with the issue. This is often the quickest and most effective way to have the issue dealt with. Enquirers are advised that if their issues are not resolved by the public authority, they can make a complaint to the Ombudsman.

For enquiries that are outside the jurisdiction of the Ombudsman, staff assist members of the public by providing information about the appropriate body to handle the issues they have raised.

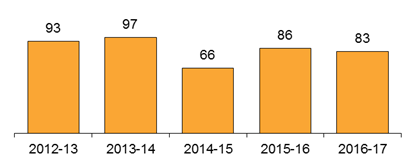

| Enquiries Received 2012-13 to 2016-17 |

|

Enquirers are encouraged to try to resolve their concerns directly with the public authority before making a complaint to the Ombudsman. |

Complaints Received

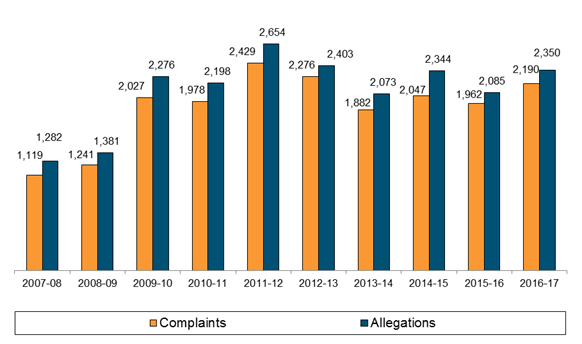

In 2016-17, the Office received 2,190 complaints, with 2,350 separate allegations, and finalised 2,169 complaints. There are more allegations than complaints because one complaint may cover more than one issue.

| Total Number of Complaints and Allegations Received 2007-08 to 2016-17 |

|

NOTE: The number of complaints and allegations shown for a year may vary in this and other charts by a small amount from the number shown in previous annual reports. This occurs because, during the course of an investigation, it can become apparent that a complaint is about more than one public authority or there are additional allegations with a start date in a previous reporting year.

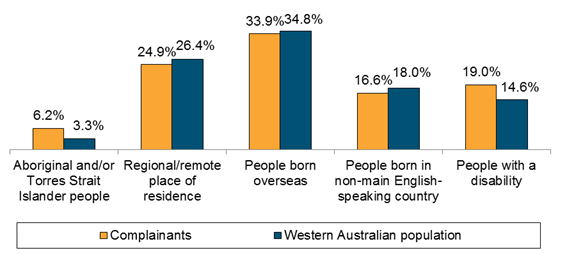

| Characteristics of Complainants |

|

NOTE: Non-main English-speaking countries as defined by the Australian Bureau of Statistics are countries other than Australia, the United Kingdom, the Republic of Ireland, New Zealand, Canada, South Africa and the United States of America. Being from a non-main English‑speaking country does not imply a lack of proficiency in English.

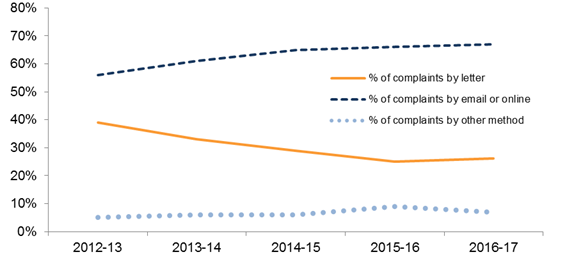

How Complaints Were Made

The use of email and online facilities to lodge complaints has continued to increase in 2016-17. The number of people using email and online facilities to lodge complaints has increased from 1,278 to 1,467 (15%) since 2012-13.

During the same period, the proportion of people who lodge complaints by letter has concomitantly reduced. The remaining complaints were received by a variety of means, including by fax, during regional visits and in person.

| Methods for Making Complaints 2012-13 to 2016-17 |

|

Early resolution involves facilitating a timely response and resolution of a complaint. |

Resolving Complaints

Where it is possible and appropriate, staff use an early resolution approach to investigate and resolve complaints. This approach is highly efficient and effective and results in timely resolution of complaints. It gives public authorities the opportunity to provide a quick response to the issues raised and to undertake timely action to resolve the matter for the complainant and prevent similar complaints arising again. The outcomes of complaints may result in a remedy for the complainant or improvements to a public authority’s administrative practices, or a combination of both. Complaint resolution staff also track recurring trends and issues in complaints and this information is used to inform broader administrative improvement in public authorities and investigations initiated by the Ombudsman (known as own motion investigations).

Time Taken to Resolve Complaints

Timely complaint handling is important, including the fact that early resolution of issues can result in more effective remedies and prompt action by public authorities to prevent similar problems occurring again. The Office’s continued focus on timely complaint resolution has resulted in ongoing improvements in the time taken to handle complaints.

Timeliness and efficiency of complaint handling has substantially improved over time due to a major complaint handling improvement program introduced in 2007‑08. An initial focus of the program was the elimination of aged complaints.

Building on the program, the Office developed and commenced a new organisational structure and processes in 2011-12 to promote and support early resolution of complaints. There have been further enhancements to complaint handling processes in 2016-17, in particular in relation to the early resolution of complaints.

Together, these initiatives have enabled the Office to maintain substantial improvements in the timeliness of complaint handling.

In 2016-17:

- The percentage of allegations finalised within 3 months was 94%; and

- The percentage of allegations on hand at 30 June less than 3 months old was 94%.

94% of allegations were finalised within 3 months. |

Following the introduction of the Office’s complaint handling improvement program in 2007-08, very significant improvements have been achieved in timely complaint handling, including:

- The average age of complaints has decreased from 173 days to 32 days; and

- Complaints older than 6 months have decreased from 40 to 2.

Complaints Finalised in 2016-17

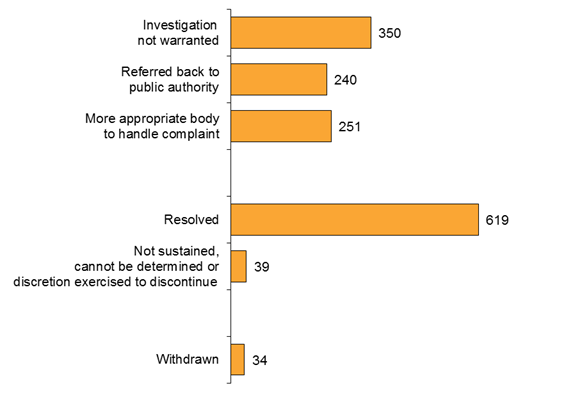

There were 2,169 complaints finalised during the year and, of these, 1,533 were about public authorities in the Ombudsman’s jurisdiction. Of the complaints about public authorities in jurisdiction, 841 were finalised at initial assessment, 658 were finalised after an Ombudsman investigation and 34 were withdrawn.

Complaints finalised at initial assessment

Nearly a third (29%) of the 841 complaints finalised at initial assessment were referred back to the public authority to provide it with an opportunity to resolve the matter before investigation by the Ombudsman. This is a common and timely approach and often results in resolution of the matter. The person making the complaint is asked to contact the Office again if their complaint remains unresolved. In a further 251 (30%) complaints finalised at the initial assessment, it was determined that there was a more appropriate body to handle the complaint. In these cases, complainants are provided with contact details of the relevant body to assist them.

Complaints finalised after investigation

Of the 658 complaints finalised after investigation, 92% were resolved through the Office’s early resolution approach. This involves Ombudsman staff contacting the public authority to progress a timely resolution of complaints that appear to be able to be resolved quickly and easily. Public authorities have shown a strong willingness to resolve complaints using this approach and frequently offer practical and timely remedies to resolve matters in dispute, together with information about administrative improvements to be put in place to avoid similar complaints in the future.

The following chart shows how complaints about public authorities in the Ombudsman’s jurisdiction were finalised.

| Complaints Finalised in 2016-17 |

|

Note: Investigation not warranted includes complaints where the matter is not in the Ombudsman’s jurisdiction.

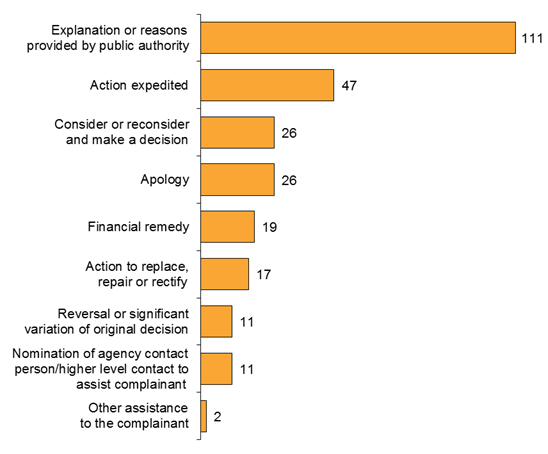

Outcomes to assist the complainant

Complainants look to the Ombudsman to achieve a remedy to their complaint. In 2016-17, there were 270 remedies provided by public authorities to assist the individual who made a complaint to the Ombudsman, an increase of 10% from 245 in 2015-16. In some cases, there is more than one action to resolve a complaint. For example, the public authority may apologise and reverse their original decision. In a further 159 instances, the Office referred the complaint to the public authority following its agreement to expedite examination of the issues and to deal directly with the person to resolve their complaint. In these cases, the Office follows up with the public authority to confirm the outcome and any further action the public authority has taken to assist the individual or to improve their administrative practices.

The following chart shows the types of remedies provided to complainants.

| Remedial Action to Assist the Complainant in 2016-17 |

|

|

| Decision reconsidered for a victim of domestic violence A woman was forced to move out of her home into a refuge due to domestic violence. As a result, the woman was not aware that her vehicle registration papers had been sent to her home address. The woman became aware that the vehicle was no longer registered when paying her driver’s licence and she was required to pay for a temporary vehicle movement permit, a vehicle inspection fee and a fine for not returning the number plates. The woman complained to the Office about the fees and fine. Following enquiries by the Office, the public authority agreed to reconsider the matter taking into account the woman’s particular circumstances. After giving further consideration, the public authority agreed to refund the fees and withdraw the fine. |

Outcomes to improve public administration

In addition to providing individual remedies, complaint resolution can also result in improved public administration. This occurs when the public authority takes action to improve its decision making and practices in order to address systemic issues and prevent similar complaints in the future. Administrative improvements include changes to policy and procedures, changes to business systems or practices and staff development and training.

About the Complaints

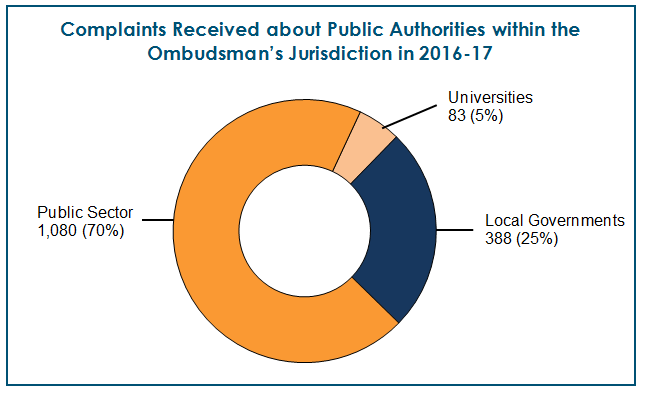

Of the 2,190 complaints received, 1,551 were about public authorities that are within the Ombudsman’s jurisdiction. The remaining 639 complaints were about bodies outside the Ombudsman’s jurisdiction. In these cases, Ombudsman staff provided assistance to enable the people making the complaint to take the complaint to a more appropriate body.

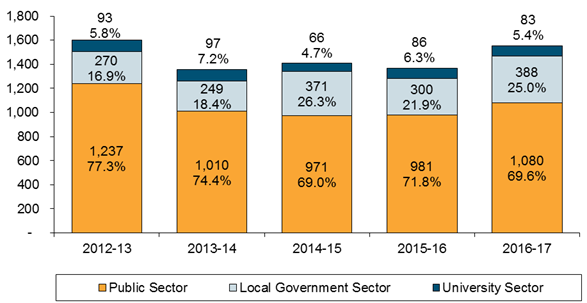

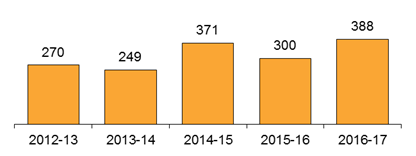

Public authorities in the Ombudsman’s jurisdiction fall into three sectors: the public sector (1,080 complaints) which includes State Government departments, statutory authorities and boards; the local government sector (388 complaints); and the university sector (83 complaints).

The proportion of complaints about each sector in the last five years is shown in the following chart.

| Complaints Received about Public Authorities within the Ombudsman’s Jurisdiction between 2012-13 and 2016-17 |

|

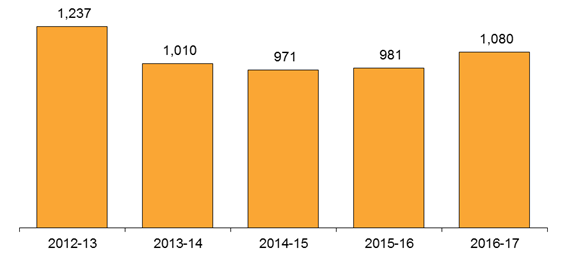

The Public Sector

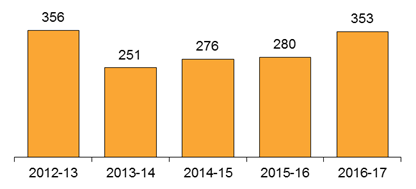

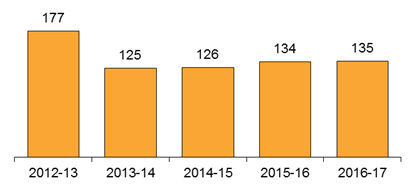

In 2016-17, there were 1,080 complaints received about the public sector and 1,068 complaints were finalised. The number of complaints about the public sector as a whole since 2012-13 is shown in the chart below.

| Complaints Received about the Public Sector between 2012-13 and 2016-17 |

|

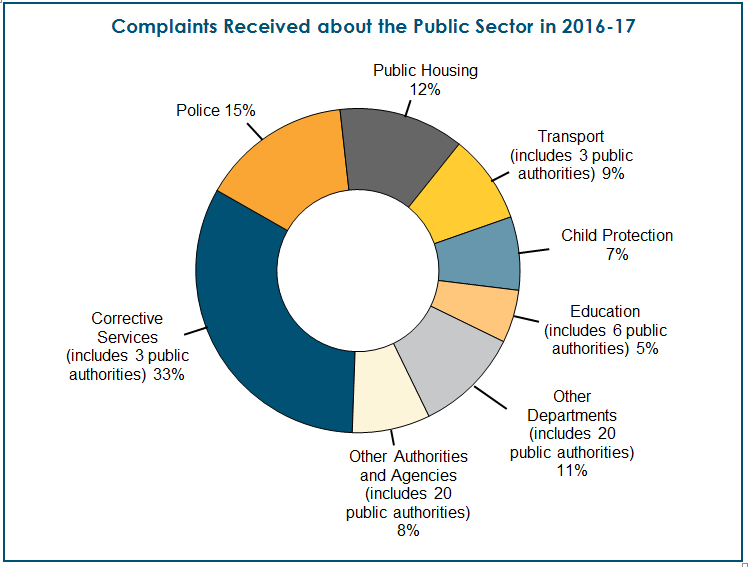

Public sector agencies are very diverse. In 2016-17, complaints were received about 55 agencies as shown in the following chart.

Of the 1,080 complaints received about the public sector in 2016-17, 81% were about six key areas covering:

- Corrective services, in particular prisons (353 or 33%);

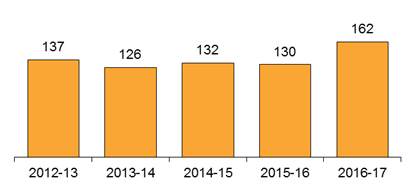

- Police (162 or 15%);

- Public housing (135 or 12%);

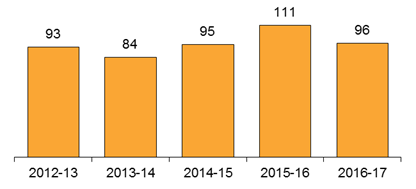

- Transport (96 or 9%);

- Child protection (79 or 7%); and

- Education – public schools and TAFE colleges (57 or 5%). Information about universities is shown separately under the University Sector.

The remaining complaints about the public sector (198) were about 40 other State Government departments, statutory authorities and boards. For 29 (73%) of these agencies, the Office received five complaints or less.

Outcomes of complaints about the public sector

In 2016-17, there were 251 actions taken by public sector bodies as a result of Ombudsman action following a complaint. These resulted in 215 remedies being provided to complainants and 36 improvements to public sector practices.

The following case study illustrates the outcomes arising from complaints about the public sector. Further information about the issues raised in complaints and the outcomes of complaints is shown in the following tables for each of the six key areas and for the other public sector agencies as a group.

|

| Application reinstated after Ombudsman involvement A person submitted an application to a public authority. The public authority requested additional information from the person to support their application and specified the timeframe for providing this information. Although the person provided the additional information within the required timeframe, the public authority withdrew the person’s application when the timeframe elapsed. The person complained to the Office about the withdrawal of the application. Following enquiries by the Office, the public authority reviewed the person’s file and found that the person had provided the information within the specified timeframe but the public authority had not placed the information on the person’s file until after the application was withdrawn. The public authority wrote to the person and reinstated their application, acknowledged the information had been received but had not been filed, apologised for any inconvenience caused and undertook actions to reduce the risk of such an error occurring again. |

Public Sector Complaint Issues and Outcomes

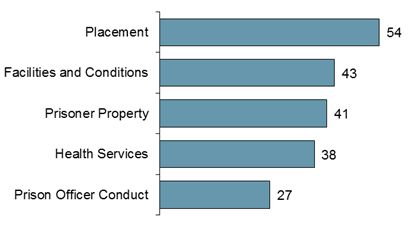

Corrective Services |

||

Complaints received |

|

|

Most common allegations |

|

|

Other types of allegations |

|

|

Outcomes achieved |

|

|

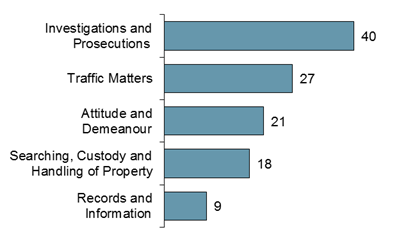

Police |

||

Complaints received |

|

|

Most common allegations

|

|

|

Other types of allegations |

|

|

Outcomes achieved |

|

|

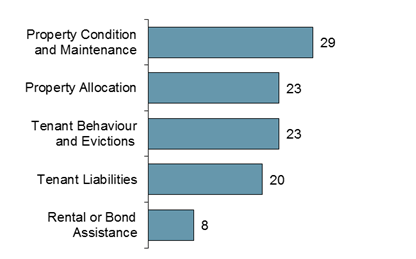

Public Housing |

|

Complaints received |

|

Most common allegations |

|

Other types of allegations |

|

Outcomes achieved |

|

>

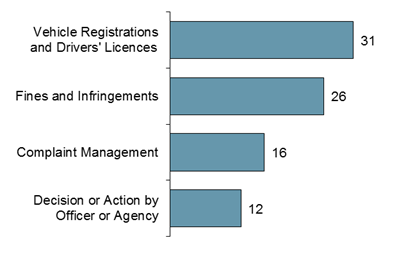

Transport |

||

Complaints received |

|

|

Most common allegations |

|

|

Other types of allegations |

|

|

Outcomes achieved |

|

|

>

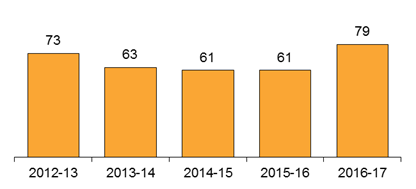

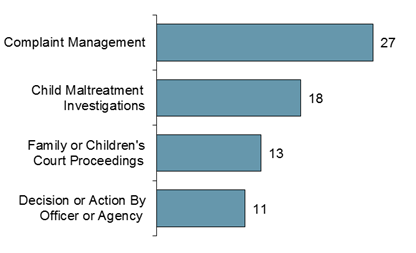

Child Protection |

||

Complaints received |

|

|

Most common allegations

|

|

|

Other types of allegations |

|

|

Outcomes achieved |

|

|

|

|

Complaints received |

|

Most common allegations

|

|

Other types of allegations |

|

Outcomes achieved |

|

Other Public Sector Agencies |

|

Complaints received |

|

Most common allegations

|

|

Other types of allegations |

|

Outcomes achieved |

|

The following case study provides an example of action taken by a public sector agency as a result of the involvement of the Ombudsman.

|

| Decision reconsidered for a victim of domestic violence A person submitted an application to a public authority for installation of a device at their property. The public authority’s approval of the request used an incorrect surname and the person wrote to the public authority twice asking that the approval be given in the correct name. When the correction did not occur the person telephoned the public authority’s complaints line and the public authority provided the correct written approval the next day, two months after the original incorrect approval was sent. The person complained to the Office about the time taken and the process required to get the correct name on the approval. The public authority reviewed the matter, acknowledged the delay in providing the correct approval, expressed its sincere regret for any distress the delay caused, and undertook appropriate actions to reduce the risk of such an error occurring again. |

The Local Government Sector

The following section provides further details about the issues and outcomes of complaints for the local government sector.

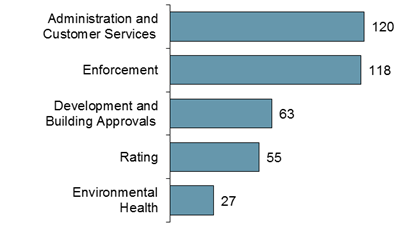

Local Government |

||

Complaints received |

|

|

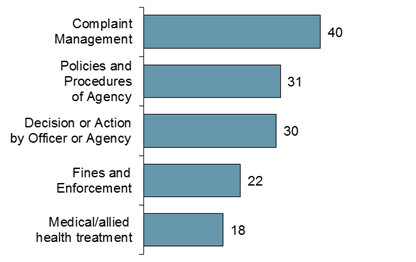

Most common allegations |

|

|

Other types of allegations |

|

|

Outcomes achieved |

|

|

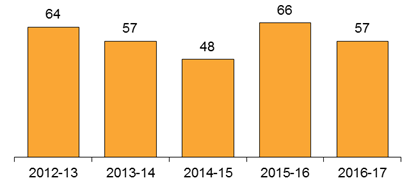

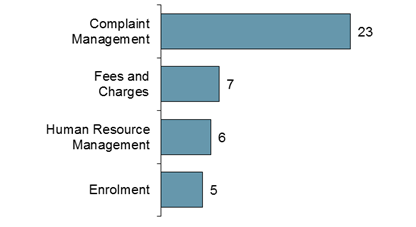

The University Sector

The following section provides further details about the issues and outcomes of complaints for the university sector.

Universities |

||

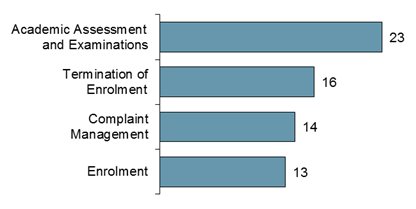

Complaints received |

|

|

Most common allegations |

|

|

Other types of allegations |

|

|

Outcomes Achieved |

|

|

|

| Decision reconsidered for a victim of domestic violence Student enrolment A student had enrolled in a master’s degree at a Western Australian university and paid a deposit for the fees but the enrolment was subject to the successful completion of a pre‑requisite unit. When they were unable to meet these requirements, the student was ‘released’ from the university, however the university withheld $1,000 of the fees already paid on the basis that it was a non-refundable deposit. After the university’s decision was confirmed on appeal, the student complained to the Office that the university had unreasonably withheld the fees. The university re-considered its decision and refunded the fees in full. The university also undertook appropriate actions to address issues of this nature in the future. |

Other Complaint Related Functions

Reviewing appeals by overseas students

The National Code of Practice for Providers of Education and Training to Overseas Students 2017 (the National Code) sets out standards required of registered providers who deliver education and training to overseas students studying in Australian universities, TAFE colleges and other public education agencies. It provides overseas students with rights of appeal to external, independent bodies if the student is not satisfied with the result or conduct of the internal complaint handling and appeals process.

Overseas students studying with both public and private education providers have access to an Ombudsman who:

- Provides a free complaint resolution service;

- Is independent and impartial and does not represent either the overseas students or education and training providers; and

- Can make recommendations arising out of investigations.

In Western Australia, the Ombudsman is the external appeals body for overseas students studying in Western Australian public education and training organisations. The Overseas Students Ombudsman is the external appeals body for overseas students studying in private education and training organisations.

Complaints lodged with the Office under the National Code

Education and training providers are required to comply with 15 standards under the National Code. In dealing with these complaints, the Ombudsman considers whether the decisions or actions of the agency complained about comply with the requirements of the National Code and if they are fair and reasonable in the circumstances.

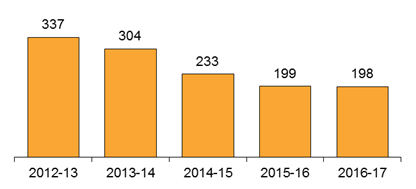

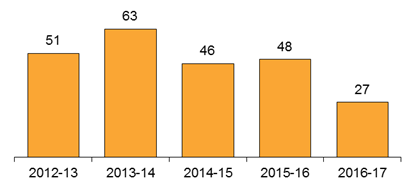

Complaints Received from Overseas Students under the National Code between 2012-13 and 2016-17 |

|

During 2016-17, the Office received 27 complaints about public education and training providers from overseas students. Twenty five complaints were about universities and two were about TAFE colleges. The Office also received seven complaints that, after initial assessment, were found to be about a private education provider. The Office referred these complainants to the Overseas Students Ombudsman.

The most common issues raised by overseas students were decisions about:

- Termination of enrolment (13);

- Academic assessment (4);

- Transfers between education and training providers (3);

- Management of academic misconduct (3); and

- Fees (2).

During the year, the Office finalised 30 complaints about 34 issues.

Public Interest Disclosures

Section 5(3) of the Public Interest Disclosure Act 2003 allows any person to make a disclosure to the Ombudsman about particular types of ‘public interest information’. The information provided must relate to matters that can be investigated by the Ombudsman, such as the administrative actions and practices of public authorities, or relate to the conduct of public officers.

Key members of staff have been authorised to deal with disclosures made to the Ombudsman and have received appropriate training. They assess the information provided to determine whether the matter requires investigation, having regard to the Public Interest Disclosure Act 2003, the Parliamentary Commissioner Act 1971 and relevant guidelines. If a decision is made to investigate, subject to certain additional requirements regarding confidentiality, the process for investigation of a disclosure is the same as that applied to the investigation of complaints received under the Parliamentary Commissioner Act 1971.

During the year, four disclosures were received.

Indian Ocean Territories

Under a service delivery arrangement between the Ombudsman and the Australian Government, the Ombudsman handles complaints about State Government departments and authorities delivering services in the Indian Ocean Territories and about local governments in the Indian Ocean Territories. There were two complaints received during the year.

Terrorism

The Ombudsman can receive complaints from a person detained under the Terrorism (Preventative Detention) Act 2006, about administrative matters connected with his or her detention. There were no complaints received during the year.

Requests for Review

Occasionally, the Ombudsman is asked to review or re-open a complaint that was investigated by the Office. The Ombudsman is committed to providing complainants with a service that reflects best practice administration and, therefore, offers complainants who are dissatisfied with a decision made by the Office an opportunity to request a review of that decision.

Fourteen reviews were undertaken in 2016-17, representing less than one per cent of the total number of complaints finalised by the Office. In all cases where a review was undertaken, the original decision was upheld.

Go to next section of the Annual Report 2016-17 >>

Go to next section of the Annual Report 2016-17 >>

Go to previous section of the Annual Report 2016-17>>

Go back to Annual Reports page >>

Download the Complaint Resolution section as a PDF

To read a pdf, you will need Adobe Acrobat Reader, which can be downloaded

for free from Adobe at http://www.adobe.com/products/

acrobat/readstep2.html.